佚名网文

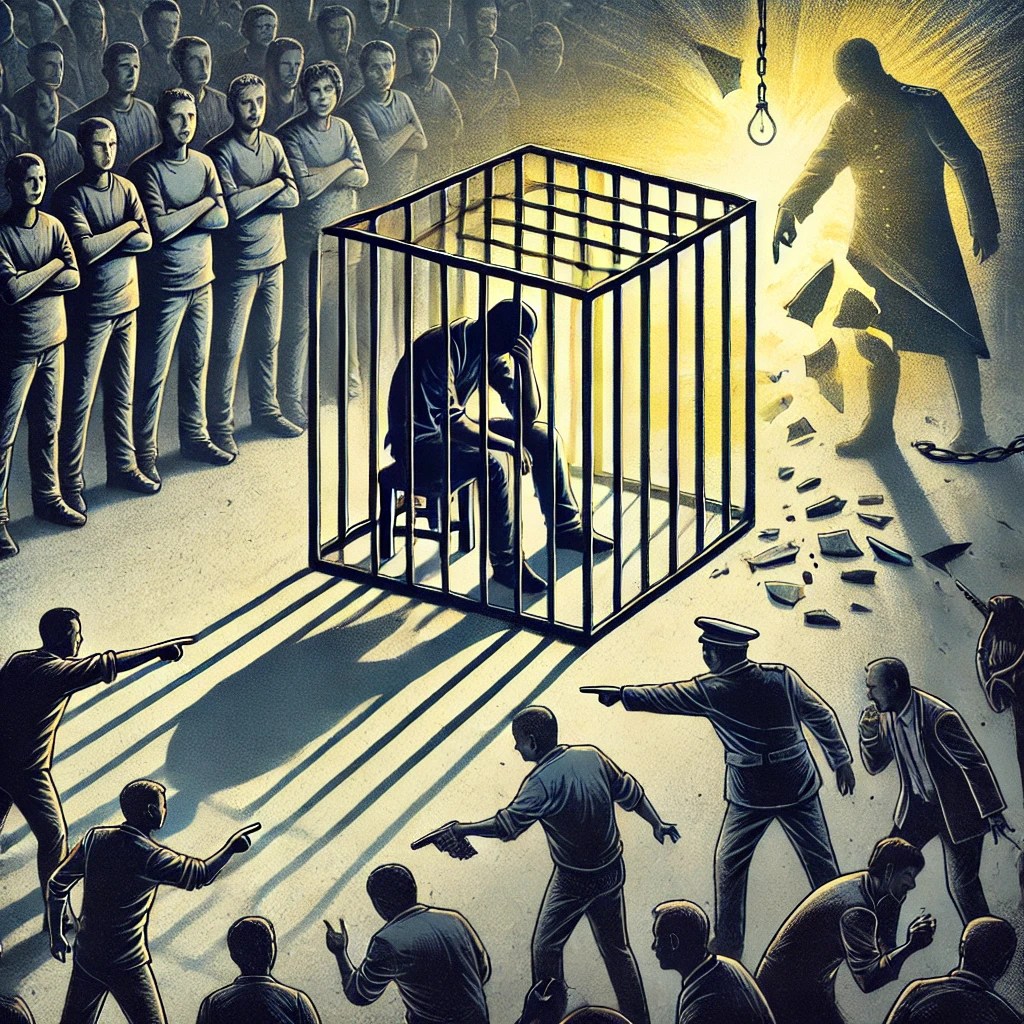

最近一篇匿名文章看似在分析民运组织的问题,实则在刻意引导舆论,制造不信任感,让人们对民主 运动彻底丧失信心。它的核心逻辑是:坐牢并不能代表正确,民运组织充满内斗,特务无处不在, 因此民运注定失败,不值得信任。这样的论调听上去似乎有理,实则是在构建一个消极无望、人人 自危的叙事,正是中共当局最希望在民主阵营中散播的情绪毒素。

文章反复暗示,“坐牢”只是某些民运人士用来获取政治资本的手段,甚至影射部分人可能是特务 刻意“塑金身”,以便更容易渗透反对派。这一逻辑荒唐得让人瞠目结舌。现实是,坐牢是一种不可 回避的牺牲,而不是可以选择的“策略”。以朱虞夫为例:1989年因参与民主运动被捕,判刑两年; 1999年因参与中国民主党,被判刑七年;2011年因再度倡导民主,被判刑七年,出狱后仍长期被严密 监控。这会是“塑金身”的安排吗?一个人会三次选择被监禁、酷刑、被剥夺所有自由去“塑金身”吗?如果坐牢是“塑 金身”,那是否意味着被虐待致死的刘晓波、曹顺利,也是在“刻意打造悲情形象”吗?

类似的污名化策略,早在前苏联、东德、朝鲜等独裁政权中早有先例:他们用“叛徒—英雄—特 务”这样的循环叙事,不断瓦解反对派,让民间社会彻底丧失信任感。

现实数据也清楚地表明,“坐 牢”的民运人士几乎没有任何经济优势。目前至少2000多名政治犯仍在中国监狱(数据来源:人权观 察2023年报告,2024年一定会更多),其中大部分人在坐牢后经济困顿,家人受牵连,流亡海外者甚至无法立足。相 反,真正的“特务”,往往能拿到绿卡、稳定经济来源,并在关键时刻“反水”或“举报”,以换取更 大政治资本。如果“坐牢=特务塑金身”,为什么这么多知名民运人士在海外仍然处境艰难,甚至靠 打工、开餐馆为生?

该文试图通过回忆社民党分裂、海外民运内部矛盾,来得出“民运组织必然走向内斗、必然失 败”的结论,却刻意忽略了一个事实:民主政治本身就是建立在不同派别竞争、对抗、协商之上的。

美国共和党最早起源于“废奴主义者”与“温和改良派”之间的激烈对抗;台湾民主运动在1980-90年 代,也经历了“美丽岛系”、“新潮流系”的激烈斗争,但最终推动了台湾民主化;香港的泛民主派过 去十年不断分裂,但每次大规模运动时,仍能团结对外。分裂不是失败,而是民主组织的成长过 程。 反观中共,党内斗争比民运圈残酷得多,仅在2023年,中共高层“肃清”运动中,就有至少20名副 省部级以上官员落马,包括国防部长、外交部长等核心人物。党内斗争导致数百万人遭清洗(1966- 1976年文革数据),但为何没有人用“共产党就是内斗”来全盘否定它的运作模式?

事实上,民运内 部分歧并非独特现象,而是所有政治组织的常态,关键不在于“分裂”,而在于是否能建立制度化的 协调机制。

文章称“和、理、非组织”天生瘸腿,无药可救。但历史和现实都证明,真正害怕和理非组织的,恰 恰是独裁政权本身。美国政治学者 Erica Chenoweth 研究了 1900-2015年间 323起政治变革,发现非暴 力运动成功率为53%,暴力运动为26%。非暴力的“天鹅绒革命”成功推翻了捷克斯洛伐克共产党; 非暴力的菲律宾“人民力量革命”推翻了马科斯政权。这些政权最终倒下,而非暴力斗争被刻意贬 低,正是因为它是更可持续、更难镇压的变革方式。

中国政府为何如此害怕非暴力抗争?1989年天安门运动、2019年香港反送中运动,最初都是非暴 力的,但政府害怕失去合法性,因此最终以屠杀、镇压收场。中共对“和理非”的恐惧,甚至超过对 暴力抗争的担忧,因为非暴力更容易赢得国内民众与国际支持,更能影响长期民意。

那么,真正“瘸腿”的到底 是谁?是“和理非”组织,还是那个连公民抗议都容不下的专制政权?

文章最后的逻辑是——任何民运组织都可能被渗透,所有知名民运人士都可能是特务,因此,我们谁都不该信。但这种“极端怀疑论”,恰恰是最符合中共统战策略的毒药。俄罗斯的克格勃 (KGB),在冷战时期最成功的“心理战”就是让流亡人士彼此怀疑,最终彻底失去组织能力。

“怀 疑一切、攻击一切、否定一切”并不能击败独裁,反而让独裁者稳固统治。 试问,当所有人都因为害 怕“被渗透”而拒绝合作,民主运动还能走多远? 真正的民主斗争,不是建立在盲目信任,而是建立在制度化的透明、监督和问责之上。盲目信任 是愚蠢的,但失去信任的政治,更是一场灾难。

如果民运有问题,那就用制度和行动去解决,而不是靠阴谋论和情绪化批判去瓦解它。这个世界上,真正渴望民运失败的,只有中共,只有独裁者。

The Reality of the Democracy Movement and the Logical Trap of Stigmatization — A Response to Recent Misguided Arguments

Anonymous Article

A recently published anonymous article appears to analyze the problems within democratic movements, but in reality, it deliberately manipulates public opinion, fostering distrust and leading people to completely lose faith in the pro-democracy cause. Its core argument is that imprisonment does not necessarily validate one’s righteousness, that democracy movements are plagued by internal strife, and that spies are everywhere—therefore, the movement is doomed to fail and is unworthy of trust. While this rhetoric may sound reasonable at first glance, it is actually constructing a narrative of despair and fear—precisely the psychological poison the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) wishes to inject into the democratic camp.

The article repeatedly implies that “going to prison” is merely a political strategy used by some pro-democracy figures to gain political capital and even suggests that some may be secret agents deliberately “building a heroic image” to infiltrate the opposition. This logic is so absurd that it defies belief.

In reality, imprisonment is an inescapable sacrifice, not a chosen strategy. Take Zhu Yufu as an example:

• In 1989, he was imprisoned for two years for participating in the democracy movement.

• In 1999, he was sentenced to seven years for his involvement in China Democracy Party.

• In 2011, he was sentenced to another seven years for once again advocating democracy.

• Even after his release, he has been under strict surveillance.

Would anyone choose to be imprisoned, tortured, and deprived of all freedoms three times just to “build an image”? If imprisonment is merely a publicity stunt, does that mean that Liu Xiaobo and Cao Shunli, who died from mistreatment, were also deliberately crafting tragic personas?

This type of stigmatization strategy has been seen before in dictatorships like the Soviet Union, East Germany, and North Korea. They use the “traitor-hero-spy” cycle to dismantle opposition movements, ensuring that civil society is consumed by distrust and suspicion.

The Reality of Political Imprisonment: No Privilege, Only Persecution

Empirical data clearly shows that “imprisoned” pro-democracy activists have no economic advantage.

As of 2023, at least 2,000 political prisoners remain in Chinese prisons (source: Human Rights Watch 2023 Report), and this number is expected to rise in 2024. Most face extreme financial difficulties after their release, their families suffer consequences, and those in exile struggle to survive.

In contrast, actual government agents often secure green cards, stable economic resources, and at crucial moments, defect or provide intelligence to gain even greater political capital.

If “imprisonment = spy strategy”, why do so many well-known pro-democracy activists face financial hardship abroad, with some working in restaurants or odd jobs to make a living?

The Inevitable Tensions Within Democracy Movements

The article attempts to portray internal conflicts within the democracy movement—such as past divisions in the Social Democratic Party (社民党) and disagreements among overseas activists—as proof that “all democracy movements are destined for internal strife and failure.”

However, it deliberately ignores an important fact: democratic politics itself is built on the foundation of competing factions, disagreements, and negotiations.

Consider historical examples:

• The U.S. Republican Party originated from conflicts between abolitionists and moderate reformists.

• Taiwan’s democracy movement in the 1980s and 1990s faced intense internal struggles between the “Formosa faction” and “New Tide faction,” yet still successfully advanced democratization.

• Hong Kong’s pro-democracy camp has fractured multiple times over the past decade, yet during every major movement, they have still united against oppression.

Divisions do not signify failure; rather, they are part of the growth process of democratic organizations.

Compare this with the CCP itself, where internal struggles are far more brutal.

• In 2023 alone, the CCP’s “internal purges” led to the downfall of at least 20 high-ranking officials, including the Minister of Defense and Minister of Foreign Affairs.

• During the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), millions of party members were persecuted.

Yet, why does no one use “CCP internal conflict” to declare the failure of its political structure?

In reality, internal disagreements are not unique to democracy movements—they exist in all political organizations. The key is not whether divisions occur but whether an institutional framework exists to manage and resolve them.

The Effectiveness of Nonviolent Movements

The article claims that “nonviolent movements” (和理非) are inherently weak and doomed to fail. However, both history and contemporary studies prove that dictatorships fear nonviolent resistance the most.

American political scientist Erica Chenoweth analyzed 323 political movements between 1900 and 2015 and found that:

• Nonviolent movements succeeded 53% of the time.

• Violent movements succeeded only 26% of the time.

Historical examples include:

• The “Velvet Revolution” that peacefully ended Communist rule in Czechoslovakia.

• The “People Power Revolution” that overthrew Ferdinand Marcos in the Philippines.

China’s own history further proves this:

• The 1989 Tiananmen Movement and the 2019 Hong Kong Anti-Extradition Bill Movement both started as nonviolent protests.

• However, fearing a loss of legitimacy, the CCP ultimately resorted to massacre and suppression.

The CCP fears nonviolent movements even more than armed resistance, because nonviolence gains public and international support and influences long-term public opinion.

So, who is truly “weak”? The nonviolent activists, or the dictatorship that cannot even tolerate peaceful protests?

The CCP’s Psychological Warfare: Sowing Distrust

The article’s final argument is that all pro-democracy organizations can be infiltrated, and all prominent activists could be spies—therefore, no one should be trusted.

This extreme skepticism is exactly the CCP’s preferred propaganda strategy.

The Soviet KGB used a similar psychological warfare tactic during the Cold War: they spread distrust among exiled dissidents, ultimately paralyzing their ability to organize.

Spreading suspicion, attacks, and total rejection of all activists does not defeat dictatorship—instead, it strengthens it.

If everyone refuses to cooperate due to fear of infiltration, how can the democracy movement survive?

True democratic struggle is not built on blind trust, but on institutionalized transparency, accountability, and oversight.

Blind trust is foolish, but a political movement without trust is doomed to collapse.

Conclusion

If the democracy movement has problems, the solution is institutional reform and action—not conspiracy theories and emotional denunciations that only serve to destroy it.

In this world, the only people who truly wish to see democracy fail are the CCP and other dictatorships.